A bit of a muddle of stuff this week. Sometimes when I write a piece I have a very clear idea of what I’m going to say. . . But not always. Hopefully it all ties together!

I posted a photo of the actor John Hamm on Instagram last week, because in this particular photo – he’s wearing jeans, an Oxford shirt and tie – he looks quite like one of the characters from my novel Bitter Sweet, Richard Aveling. Richard is a 56 year old married author, who draws our young protagonist, 23 year Charlie, into an affair.

So many people in the community there are early readers of Bitter Sweet, either as reviewers, bloggers, publishers or friends. Many of them thought that Hamm was far too attractive to be Richard, and I guess they are probably right. But I see him more from Charlie’s point of view, and she doesn’t really, truly see him as he is until the end of the book — this is not a spoiler, there is a prologue. Charlie is totally infatuated with Richard, a ‘complicated man’, seeing a mirage of the younger version of him that appears on his earlier book jackets. In these photos, he is closer to her age of 23, not 56.

I think we’ve all been there; caught in a state of limerence we are unable to see the truth of someone. We imagine them to be someone that they are not, both in terms of their physicality and nature, and only when we are free of our infatuations are we able to really see the person for their faults. Even the very smartest people have felt that. Romantic love, in all of its forms, is a total fucker. It makes for great literature.

Many people shared who they imagined as Richard; there was a lot of Jeremy Irons. A few people (Christa!) messaged to say, affectionately, that I wasn’t to ruin John Hamm for her by muddling him with someone as awful as Richard, which made me laugh because I have just rewatched Mad Men and Don Draper really is an arsehole, isn’t he? The epitome of a ‘complicated man’. But yes. A ‘fixable arsehole’, as clever Christa put it. (She is a very smart and intuitive person.) Time has aged how we perceive Don Draper, who is truly one of the most masterfully drawn characters in television history. A baddie we all adore, a lovable rogue. A complicated man, forgiven endlessly by the audience because he’s so nice to look at.

(The opposite is, of course, the unlikable female character. More on that trope soon.)

When I posted that picture, I was probably making an unfair association between John Hamm and Don Draper, seeing some of the latter in my character, Richard Aveling. I recently had a conversation with a younger friend who was watching Mad Men for the first time and Draper’s misogyny, even in the historical context of the show, was unbearable to the point of being unwatchable for her. I thought this was really interesting. Maybe things have changed? Maybe not. I don’t know. I hope so.

The Richard of my book is actually based loosely on the very badly behaved, but undoubtedly genius, late English poet Ted Hughes. I used a line from Hughes’ poem from Birthday Letters, ‘Child’s Park’, as the epigraph of Bitter Sweet. There is a lot of the poet and author Sylvia Plath (she was married to Hughes) in Charlie. Plath and Hughes’ relationship has always fascinated me, and broken my heart. He certainly broke Sylvia’s, irreparably. Ted was a ‘complicated man’, to put it lightly, but his writing is extraordinary.

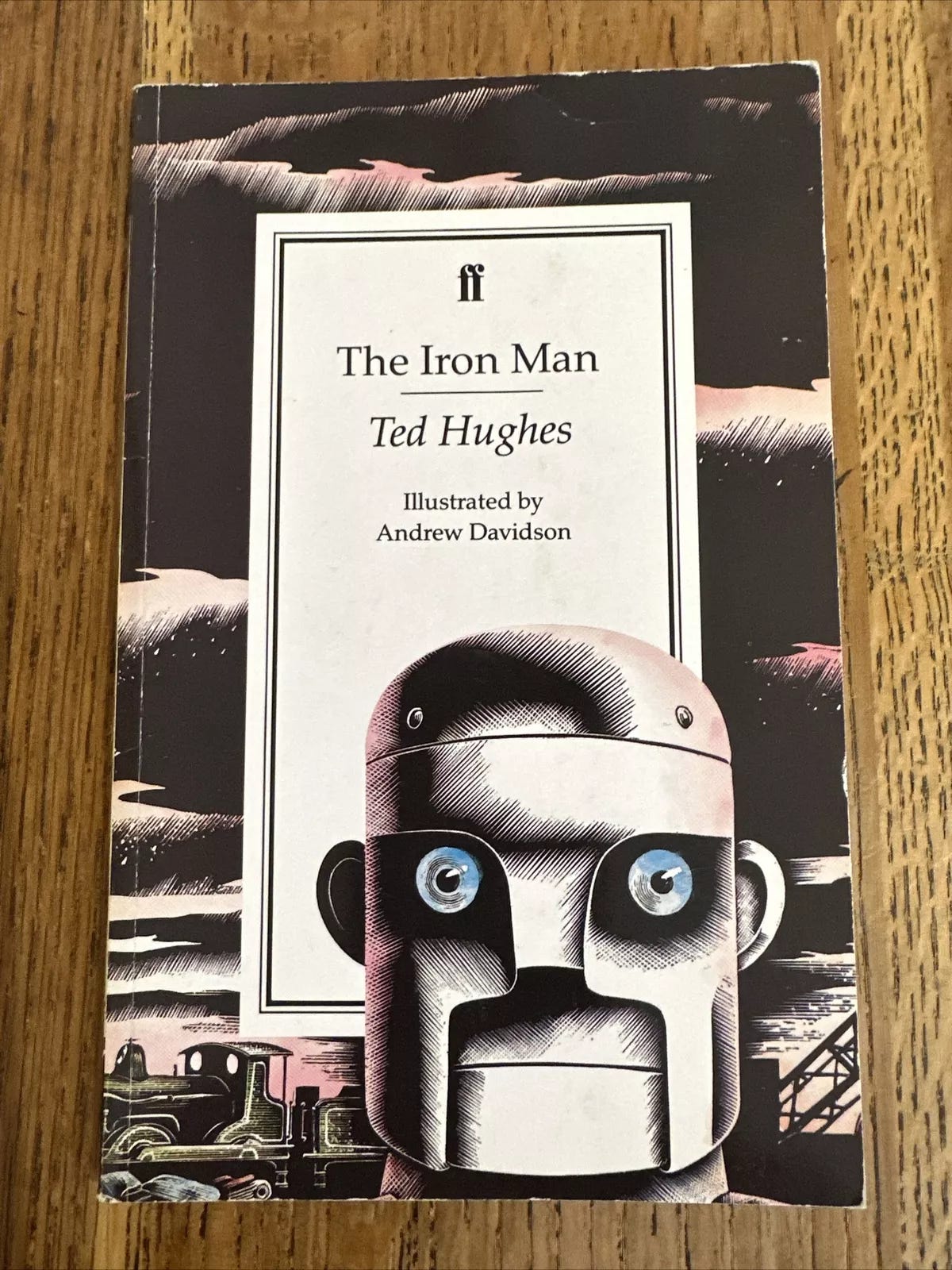

I learned to read very early (thanks Mum) and I distinctly remember reading Hughes’ children’s book The Iron Man when I was really small. My classmates were on Biff, Chip and Kipper but I was allowed to go the school library and choose a chapter book. I chose it probably for the illustrations, but it had a profound impact on my young mind. It was so strange and melancholy. It hit upon the very tender kind of loneliness that only a child can feel. I actually think it really set the tone for all the art I would go on to love.

Indeed, Hughes’ poetry collection Crow is amongst my favourite books of all time, and it is also why I’m so enamoured with Max Porter’s Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. Hughes wrote about grief so intimately, I guess because he knew it so well — both Sylvia, and later his partner Assia Wevill, died by suicide. Assia also killed their child, Alexandra Tatiana Elise, known as ‘Shura’. The tragedy is hard to comprehend. Even writing these words makes my heart ache.

How he treated these women is disputed.

The lives and deaths of Plath and Wevill of course demand that we ask the question of where we draw the line between the art and the artist. This is a theme of Bitter Sweet. I do not believe (generally — there are a few exceptions) that we should ignore brilliant art because of the actions of the artist. We’d be excluding a lot of the classics if we did. There is so much we can learn from Hughes’ work. It teaches us about everything from the natural world to our capacity for darkness as human beings and the way that he does this, his use of language, is beyond my technical understanding. I am no academic or scholar — I don’t even have a degree — but the way his writing moves me as a reader is fuckin’ wild, and profound. I feel that we must instead consider Ted Hughes the man, his behaviour and and his (disputed) actions in life alongside his work.

The Richard that I imagined when I wrote Bitter Sweet will be different from the Richard my readers imagine. As will the front of any building I describe, or the smell of a room, the taste of a cup of coffee. It is no failure of the reader or the writer if what we imagine is different. Because the story only really exists in the space between us.

This is not an original thought, of course. It is the very essence of literature.

I believe that reading is an enormously curious and creative act. It’s kind of radical, too, in that a book can completely change you, and as a reader you likely go into a novel knowing that this is a possibility. A scene that you imagine particularly vividly can feel indistinguishable from your own memory; I’d love to understand the neuroscience of that, if anyone knows.

Stories, prose, poetry, plays, whenever we absorb them, we are connecting words with our own memories, with our internal worlds, and building something inside of us, as I did all those years ago with The Iron Man.

It is just five weeks until Bitter Sweet is published, and I look forward to having bigger conversations then about how readers imagine my characters, and the places they inhabit. To be able to build worlds inside of the heads of readers is an enormous privilege. Reading a book is a major commitment of time and energy and empathy on the part of the reader. I very much hope that my story makes good use of all of it.

If you liked this, then please pre-order my debut novel Bitter Sweet which is out on July 3rd in the UK and Commonwealth/July 8th in the US. You can find out more about it and me HERE. Pre-ordering is the single biggest way you can support an author. I will be eternally grateful!

BIG FEELINGS RECOMMENDS

This week I have been loving:

The astonishingly good novel AND NOTRE DAME IS BURNING by Miriam Robinson which is breaking my heart and putting it back together again piece at a time. The beginnings and ends of marriage, betrayal, youth, the female experience, motherhood — it has it all, and written with such beauty and grace I can’t get my head around it being a debut. If you like Miranda July and Claire Kilroy you’ll be into this. It is out in early August, so and pre-order it now

This LANEIGE LIP SLEEPING MASK

This piece on The New Yorker about psychedelics and religion - THIS IS YOUR PRIEST ON DRUGS

Supermarket peonies. Peonies are the undisputed queens of the flower world and this short, joyous season, and their individual short lives, must be indulged.

Love the line in here, “It hit upon the very tender kind of loneliness that only a child can feel’” There’s a nostalgia pang to that, perhaps because I can no longer tap into it.

Big fan of Jon Hamm being in the film.